These Related Stories

Bank Failures in Context – Slivergate, Signature, and SVB

Share this

Over the last couple of days, we have seen a media storm about recent bank failures and how these failures may (or may not) signal upcoming bank runs and a crisis in the overall financial system. Is there any truth to this media blitz or is it just more run-of-the-mill fear mongering to boost ratings?

There is no crystal ball when it comes to this stuff and one can never be sure of an outcome, but with that said, let’s dive into the data and see what we can determine.

Historical Context of Bank Failures:

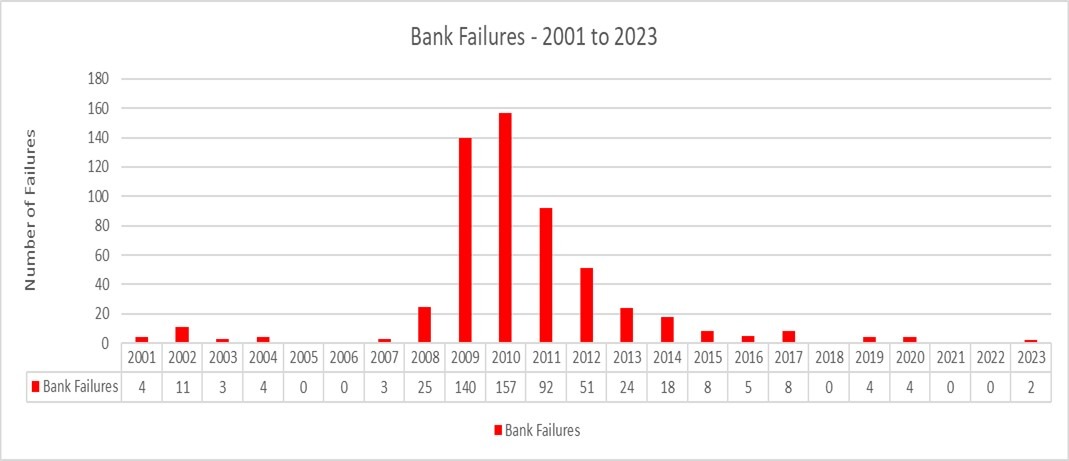

There is no doubt that the media has latched onto the recent bank failures and would have us believe that these occurrences are some sort of never-before-seen phenomenon. The truth of the matter is that bank failures are quite commonplace and happen almost every year. In fact, according to the FDIC, since 2001, there have only been five years with no bank failures whatsoever.[i] In Figure 1 below, you will see a breakdown of those bank failures by year.

Figure 1:

As you may have noticed in Figure 1 above, the bulk of the 563 bank failures from 2001 to 2023 took place during and directly after the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) between 2008 and 2012.[ii] Even if we eliminate those years from our analysis, we still average just over five bank failures per year. Even in a year like 2017, where we experienced solid economic growth and very little financial turmoil, there were still eight bank failures.[iii]

Bank failures are not a new development and the recent media coverage of the topic has no real meaning in and of itself.

Timing of Failures:

The current narrative is that “this is the beginning of a larger banking crisis” and, if true, that is a very scary prospect. We all remember the pain of the GFC and the long road back from that severe economic downturn. However, if the bank crisis is caused by systematic problems and is more widespread, banks really won’t start failing on a mass scale until after those systematic problems have become apparent. The reason for this is because banks are big, lumbering beasts and it takes a long time for the systematic economic effects to show up on their balance sheet.

If we look at the many bank failures that occurred during the GFC, we don’t see the failures happening in 2007, before the recession really took hold. In fact, we don’t really see a significant uptick of failures until 2009. The technical recession during the GFC took place from Q4 2007 to Q3 2009, but the bulk of the failures happened after the recession was actually over.[iv],[v]

From an investment standpoint, these bank failures really started happening after the technical bear market bottom, which occurred on March 9th, 2009. If you used bank failures as a data point to make your investment decisions, you would have missed out on one of the steepest bull market recoveries in history, as the S&P 500 Total Return rose over 70% in the subsequent 12 months.[vi]

If we really start to see an uptick in bank failures, it won’t signal the beginning of a recession, but rather that we are likely most of the way through one. In other words, bank failures are much more of a lagging indicator than a leading indicator.

Systematic or Mismanaged:

The key to determining whether there are a slew of bank failures around the corner, or if this is just another typical year, is to figure out if the problems faced by Silvergate, Signature, and Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) were systematic and will affect other banks in mass or if these issues were simply the results of mismanagement. Let’s take a deeper dive.

It is important to note that it is still very early in the bank liquidation process. As a result, not all of the details related to these failures are public knowledge yet. This analysis is based on the most current information available to our team.

Silvergate Bank:

Silvergate is a very interesting bank, as it focused its services primarily on crypto and crypto-related businesses. In fact, one of Silvergate’s biggest clients was FTX, which is now bankrupt and continues to be under investigation for fraud. Since the end of 2021, most crypto tokens have fallen in value by 60% to 70%. This devaluation hurt a large majority of Silvergate’s clientele and, eventually, this weakness bled through and showed itself on Silvergate’s balance sheet. Then, on March 8th of 2023, Silvergate essentially saw the writing on the wall and began a voluntary discontinuation of business with a plan to return all deposits to its depositors.[vii] Silvergate is a perfect example of how it takes time for problems to really start to show on a bank’s balance sheets. The crypto rout began in late 2021, but it took about 14 months before Silvergate announced that it would be shutting its doors.

In our analysis, it wasn’t broad systematic problems or severe mismanagement of the business that led to Silvergate’s demise, but more of an issue with their business strategy. They hitched their wagon to the crypto horse and that horse didn’t make it very far. You could argue that, if it wasn’t for the FTX fraud, Silvergate may have continued operations, but hindsight is always 20/20.

The real question at hand is: are the underlying factors that caused the Silvergate failure contagious, and will that have an impact on a broader set of banks? Put simply, no. there will be some other banks effected by the problems in the crypto space, but it will be a narrow sliver of the overall banking industry. Which leads nicely into the next analysis…

Signature Bank:

Signature, like Silvergate, was one of the few banks that serviced crypto and digital asset clientele. They launched their digital asset services in 2017, when they had roughly $33 billion in assets. Since that time, they have more than tripled their total assets to over $100 billion.[viii] Although Signature claimed, in December of 2022, that deposits from operators in the digital asset space only accounted for 23% of total deposits (which is still very high), it’s hard to imagine that number wasn’t far higher.[ix] And, like Silvergate, they had a lot of involvement with FTX, which damaged their brand.

From an asset perspective, Signature’s balance sheet was fairly strong, as they carried less than 10% of held to maturity securities, and most of their assets were short term in nature and very liquid.[x] However, almost 90% of the deposits held by signature were above the FDIC limits, meaning they were effectively uninsured.[xi] This is primarily due to the fact that digital assets, and the more speculative types of companies that Signature served, had nowhere else to put their money. In other words, they effectively put all their eggs in one basket.

Ultimately, Signature Bank, although much more diversified than Silvergate, served a more speculative niche of the market. When SVB failed (which we will cover next), Signature’s narrow customer base got antsy and withdrew more than 20% of their total deposits in a single day from the struggling bank. It was the combination of the customers that Signature chose to serve and the fact that this particular clientele did not have many options for where to store their money that led to the bank run and, ultimately, Signature’s failure.

Think about it this way, if you were only able to use a single bank for your entire life savings and then a bank just like it failed, would you let the money sit or would you get it out as fast as humanely possible?

Meanwhile, there is continued speculation that the bank didn’t actually need to be shuttered, but was closed to send a message by regulators who wanted to show that they are serious about regulating the digital space. We will likely never know.

Just like with Silvergate, our analysis is that the failure of Signature was not due to systematic problems, but rather a strategic decision that did not play out how the bank had hoped. The strategy benefited them greatly from 2017 to 2022, but became their undoing over the last 14 months. That’s not to say that asset pricing, interest rates, and the Net Interest Margin didn’t also play a role, we just don’t think that these factors played as large of a role as the media would have us believe.

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB):

Now, we get to the largest (and likely most important from a macro perspective) of the three recent bank failures: Silicon Valley Bank (more commonly known as SVB).

Silicon Valley Bank has been around since 1983 and was a financial services staple of the tech industry.[xii] Compared to Signature and Silvergate, SVB was a behemoth with a little over $200 billion in total assets, making it the 16th (or thereabout depending on the source) largest bank in the United States.[xiii] Even though those are very large numbers, it was by no stretch of the imagination one of the largest or most influential banks in the US. In fact, SVB was considered a “mid-sized” bank. For comparison, the largest bank in the US is JP Morgan Chase, which holds approximately $3.7 trillion in total assets.[xiv] That’s not a typo, “trillion” with a T.

SVB has focused its business on venture capitalists, start-ups, and the tech industry as a whole. Even its website, which has now been taken over by the FDIC, focuses its language and content almost entirely around these groups, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2:

This highly focused strategy deployed by SVB had been very lucrative in the past, especially over the last few years. For example, SVB almost doubled its total assets in 2020, growing from roughly $115 billion to over $200 billion in a single year (does this seem reminiscent of Silvergate?).[xv] That is simply extraordinary growth for a bank of this size. In fact, it’s basically unheard of. This level of growth was primarily due to the COVID-era tech bubble, as start-ups were coming out of the woodwork. The problem is that this area of tech would prove to be quite unstable, especially as the world began to return to normal. The crypto and digital asset boom slowed to a crawl and all these small tech companies saw their revenue simply dry up, if they even had it in the first place. Unfortunately, these were the clients of SVB and, accordingly, the bank experienced almost zero growth in 2022.[xvi] That is quite a change from its previous years and something that I do not think management was expecting. The fact that this space experienced a significant slowdown meant that, instead of adding to the funds held at SVB, they were pulling funds out to meet payroll and expense obligations. After all, these types of companies have a very high burn rate.

The immense growth experienced by SVB gave management an increased appetite for risk, which can be seen on the bank’s balance sheet. At the end of 2022, roughly 43% of SVB’s assets were classified as held-to-maturity securities.[xvii] Held-to-maturity (HTM) securities are not meant to sell. As their name suggests, they are meant to hold until they mature, at which point they would pay back the original principle paid. When an HTM security is sold to cover withdrawals, it requires all other HTM securities in that class to be marked down to the most recent market price, essentially reclassifying them as “available for sale”. Put simply, SVB was so confident in their ability to keep growing and collecting additional deposits that they purchased securities that paid them a higher return, but may have been more volatile. This is what is referred to as a “reach for yield” and it rarely ends well. For comparison, JP Morgan Chase holds approximately 11% of their assets in HTM securities.[xviii]

As the withdrawals continued to pile up, SVB had to figure out how to return money to its depositors, so on March 8th of 2023, they decided to attempt a capital raise in the amount of $1.8 billion.[xix] This is where everything began to go downhill, fast. There is a lot of speculation as to the events of the subsequent few days, but the common narrative is that the message conveyed by the potential capital raise panicked depositors. What happens next is very unlikely to occur in a bank with a more diversified depositor base, but on March 9th of 2023, there were $42 billion in attempted withdrawals that forced SVB to liquidate a chunk of their HTM securities and left them with a cash shortfall of $958 million.[xx] It was at this point that regulators stepped in and turned the bank over to the FDIC.

What Caused the Run on SVB?

As we have outlined above, SVB had a very concentrated depositor base that was primarily comprised of tech startups and venture capitalists. These depositors are a tight-knit group. In addition, it wasn’t just the businesses themselves that had deposits at SVB, it was their employees, friends, and family members as well. These depositors were also quite wealthy and, in many cases, had deposits well in excess of the $250,000 FDIC insurance limit. In fact, about 93% of SVB deposits were in excess of the FDIC limit (again, does this remind you of another bank…hint, hint).[xxi] When the capital raise was announced, it spooked these firms, which held so much money with SVB. As a result, these firms reverberated the message to withdraw funds from SVB to everyone in their organization, including employees, friends, and family members. It appears that message was received, resulting in massive withdrawals occurring in a single day.

Systematic or Mismanagement?

Based on our analysis, what happened to SVB is not a systematic problem, but, again, a strategy and management problem. SVB made a conscious decision to take a high level of risk on both the front and back end. They catered to a very narrow group of depositors and took additional risk reaching for yield on the investment side. These decisions paid off enormously just a few years ago, but ultimately led to the demise of SVB. Interest rates did play their part in the undoing of SVB, but ultimately the effects of rising rates could have been mitigated with proper risk management, but simply weren’t. The mantra of Silicon Valley is “grow or die” and, in SVB’s case, they were able to attain both in a very short amount of time.

Bank Failures – The Macro Picture:

In our view, the bank failures are not systematic, but there are systematic variables (interest rates) at play that contributed to these failures, which is why everyone is so concerned about a potential contagion. These banks were all mismanaged (fairly obviously) and the failures could have easily been avoided.

Will there be more bank failures? Of course there will. As we mentioned previously, banks fail almost every year and this year will be no different. Rising interest rates will expose banks that have been mis-managed and these banks will certainly face difficulty and maybe a few more will fail. Bank runs, in and of themselves, can be a self-fulfilling prophecy and for these mismanaged banks, it may be a tough storm to weather. Although this is difficult for depositors and employees of these institutions, it is not necessarily a bad thing for the long-term health of the overall banking industry. Occasionally, the herd must be culled to make it stronger and more agile.

In the meantime, individuals and the media are going to continue the witch hunt to find the next SVB and do everything they can to make parallels to 2008, Bear Stearns, and Lehman Brothers. The reality is, however, that banks, as an industry, are about as strong as they have ever been. Making a true contagion very unlikely.

A Note on Policy:

US regulators have opened up loan facilities that allow banks to borrow money against their HTM securities at par value, so they do not have to sell them. This is a dangerous game because it may incentivize more risky behavior by banks if they believe that they will never have to sell HTM securities. With that said, in the short term, this will likely instill some confidence and help prevent potential bank runs, but it must be dealt with quite delicately. We will continue to monitor the banking industry for new developments.

Additionally, regulators have decided to fully reimburse all depositors at SVB and Signature Bank, which is great for depositors, but potentially very bad for small- and mid-sized banks. The decision to make depositors whole in this situation is based on an arbitrary measure of the bank being “systematically important”. Put more bluntly, banks that are determined NOT to be systematically important will not receive this same treatment. In the short term, it is possible that this will induce additional bank runs on small banks. In the long run, it highly incentivizes depositors to keep their money at the largest banks. If this line of decision making continues, it won’t be long until the big banks get bigger and the small banks get smaller or simply go away.

Think about it this way, if you have a few million bucks or more, are you going to put that money in a large bank, in which the government will guarantee every penny, or The Oakwood Bank of Texas?

What it Means for Investors:

The media has really latched onto these bank failures and made them appear very frightening. Why they never publicize other bank failures is beyond us, but they have done a phenomenal job of fear mongering based on recent events. However, media blathering does not make these failures any more of a systematic problem. Banks, in general, are in pretty good shape. In the short term, you never know what stock and bond markets will do, but it is likely that financials and regional banks will experience a higher level of volatility than other areas of the market (on both the up and downside). In the long term, the economy keeps chugging along and, even if we have a recession in the near term, that is already priced into markets.

If you have a well-diversified portfolio and solid financial plan, then now is the time for patience and discipline, not rash decision making based on the most recent headlines. This too shall pass.

About the Author

Ben Lies is the Owner and Founder of Delphi Advisers, LLC. He was born and raised in the Pacific Northwest, which is where Delphi Advisers is headquartered. Ben is a sports enthusiast and was an intercollegiate athlete, but his passion is investing and economics. He has been involved with investment analysis for about 20 years and has been working directly in financial services for the better part of a decade. He holds a Bachelors Degree in Business from the University of Washington, an MBA in International Business from Portland State University, and a Certificate in Business Strategy from Cornell.

Did you know XYPN advisors provide virtual services? They can work with clients in any state! Find an Advisor.

Share this

- Good Financial Reads (925)

- Financial Education & Resources (892)

- Lifestyle, Family, & Personal Finance (865)

- Market Trends (114)

- Investment Management (109)

- Bookkeeping (55)

- Employee Engagement (32)

- Business Development (31)

- Entrepreneurship (29)

- Financial Advisors (29)

- Client Services (17)

- Journey Makers (17)

- Fee-only advisor (12)

- Technology (8)

Subscribe by email

You May Also Like

Counterintuitive Lessons from a Downturn

2022 Was Tough for Investors, Will 2023 Be Better?